What Lady Gaga fans taught me about LLMs

A few weeks ago, I found myself working on a technically ambitious project with an unexpectedly emotional motivation: build a system capable of competing in a large trivia event where the prize was a pair of VIP tickets to a Lady Gaga concert. The quiz promised fast-paced questions, a strict timer, and a scoring mechanism that rewarded not just accuracy, but the speed of each response. And after speaking with one of the organizers, I confirmed something crucial: online searches and external tools were explicitly allowed. The competition would be determined by reflexes and, of course, knowledge in Lady Gaga.

What I quickly discovered, however, was that I would not be competing only against individuals. Gaga’s most dedicated fan communities were preparing to take the quiz together, coordinating answers and sharing knowledge in real time. That collaboration raised the bar significantly. Beating a single expert is difficult; keeping up with an organized group of them is another challenge entirely.

Building a Retrieval System Under Time Pressure

The first prototype was a standard LLM answering pop culture questions. It struggled. General-purpose models perform well across broad domains, but their accuracy drops when trivia requires deeply specific, long-tail knowledge. The initial score hovered ~51%, far below what I needed.

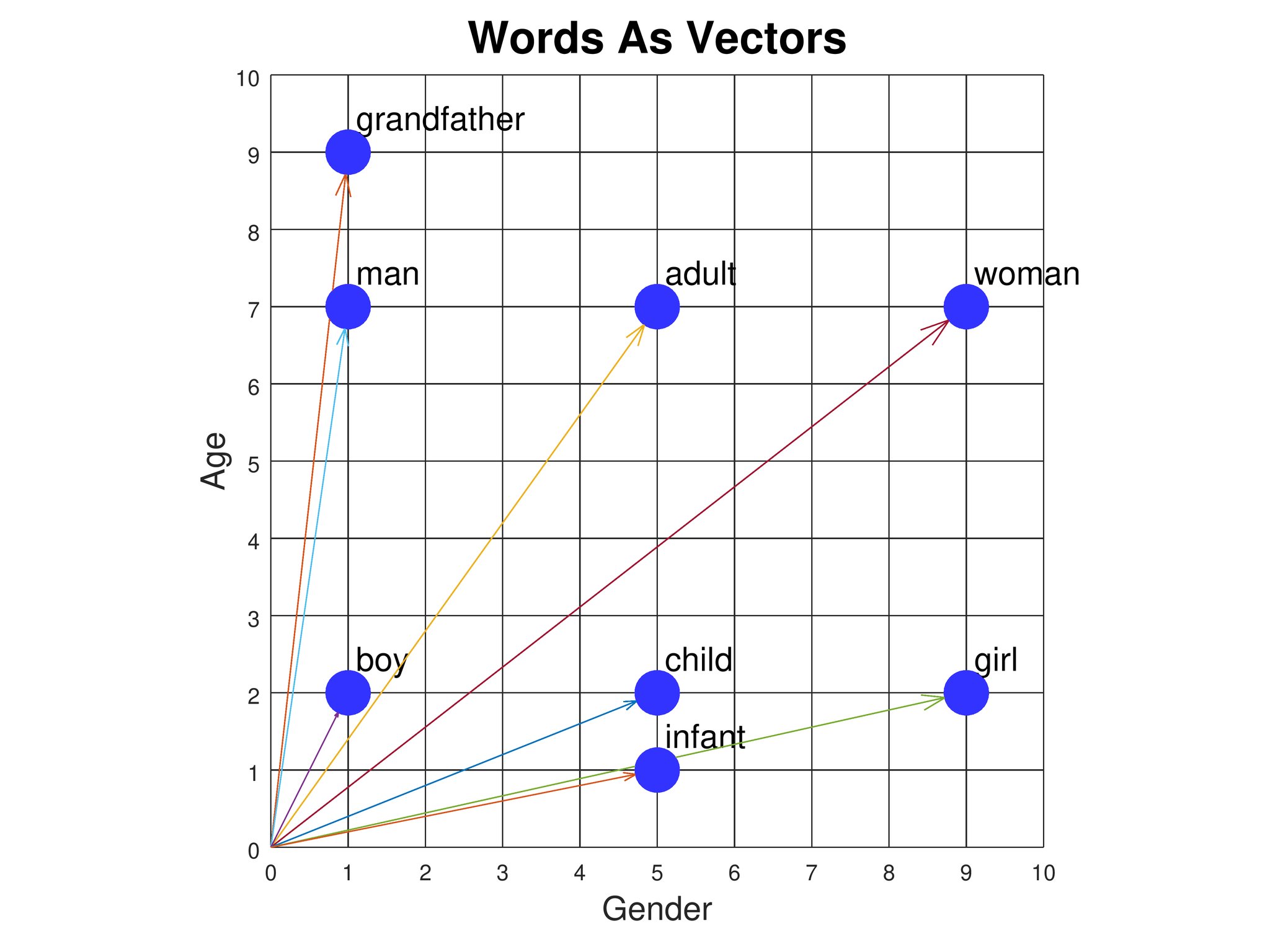

So I turned the project into a retrieval problem. I built a crawler that collected more than 8,000 articles from the Lady Gaga Fandom Wiki, assembling a domain-specific archive that covered albums, performances, behind-the-scenes notes, stylistic eras, and an impressive amount of community-maintained metadata. Using embeddings, I mapped the entire corpus into a 384-dimensional vector space, allowing the system to surface the most relevant passages in milliseconds.

Retrieval-augmented generation consistently lifted the model’s accuracy to around ~72%. Importantly, the system could now pull, synthesize, and answer within the one second latency budget imposed by the quiz mechanics. In terms of engineering, it was a compact but capable pipeline: a fast vector search, contextual augmentation, and a language model tuned for short, direct outputs.

Still, it wasn’t enough.

The Irreducible Advantage of Human Experience

The top participants (many entering the quiz collectively, sharing insights as the questions appeared) regularly scored above 80%. Their advantage wasn’t just collaboration; it was something harder to quantify.

As I reviewed the questions, a pattern emerged. Many of them depended on knowledge that simply does not exist in textual form online. They referenced fleeting visual details in music videos, context from old interviews, or information that lived inside the fan community rather than in any openly indexed source. Even with the entire fandom wiki embedded and ready to be queried, the system had no path to the correct answer if the underlying information had never been written down.

This was the boundary I couldn’t cross. The retrieval layer was precise, the inference was fast, and the architecture behaved exactly as it was designed to. But it could not synthesize knowledge that the internet itself does not contain. Meanwhile, the fans, drawing on years of observation, memory, and shared history, operated far beyond what a text-trained model could reconstruct.

A Practical Lesson About Current LLM Limits

Losing the competition wasn’t the outcome I hoped for, but the experience clarified an important point about modern AI systems. LLMs operate predominantly over textual, explicitly documented knowledge. No matter how sophisticated the model or how carefully engineered the retrieval system, the upper bound of its capability is set by what humanity has chosen to write down, publish, and make available to be crawled.

Large areas of human expertise remain informal, tacit, experiential. They live in observation, in personal memory, in countless micro-interactions with culture that never become words. Fans know the color of a nail polish in a music video not because they read it somewhere, but because they saw it. And current LLMs cannot meaningfully internalize knowledge that was never text to begin with.

This project, though designed for a very specific purpose, underscored a broader truth:

LLMs cannot retrieve what the world has not documented. And an extraordinary amount of human knowledge is still undocumented (!!)

Until models are able to combine text with genuinely robust multimodal understanding, persistent memory, and the ability to learn from non-textual context, they will continue to encounter hard limits in domains where the decisive information simply isn’t written anywhere.

Even though I ultimately failed in my attempt to secure the VIP tickets, the effort itself still mattered. My partner was genuinely happy with how far I went trying to create a better experience for her, and I was grateful for the chance to confront, in practice, a limitation of LLMs that I had never clearly seen before.

Note: This post is adapted from a Twitter thread I originally wrote about this experiment. You can read the original thread (in portuguese) here.